Since I will be running at high altitude in the Volcano Marathon, and have never been at altitude, let alone run at altitude, I jumped at the opportunity to do some hypoxic training. It is not about performance or improving performance, it is simply for me to get a feel for how my body will react, and set my expectations based on how I respond.

There will be those of you out there who will be thinking ‘man up’ just get out there, take it as it comes and pick up the lung that you coughed up on the way over the finish line. The problem with that is that I am a planner and I like to be prepared. If I know what is coming I will not panic and will be more likely to take it as it comes and cope with it. It will hopefully prevent or less the ‘fight or flight’ response that I get when something unusual or unexpected happens.

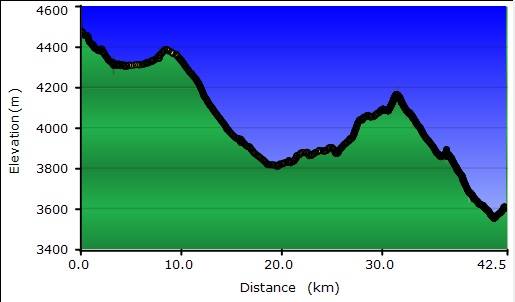

The volcano marathon starts at a height of 14,500 ft. drops to 12, 500 ft., climbs back to 14,000 ft. before finally descending down to just below 12,000 ft. At that height the air will be thin and the effects of altitude will be felt. At the start there will be about 59% of the oxygen available at sea level: 11% oxygen molecules.

As you go up a mountain, the air becomes less compressed and is therefore thinner. The effect of this decrease in pressure is that in a given volume of air, there are fewer molecules present. The percentage of those molecules that are oxygen is exactly the same: 21%, but the problem is that there are fewer molecules of everything present, including oxygen. So although the percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere is the same, the thinner air means there is less oxygen to breathe.

A few days acclimatisation is a mandatory requirement for the Volcano Marathon and competitors must arrive in San Pedro three days prior to the race to allow our bodies to adjust. Our breathing will become faster and deeper to take in more oxygen and we might feel short of breath when running during the first couple of days at our base in San Pedro de Atacama. By race day, we should be somewhat adjusted to the altitude having spent 3 days at almost 8,000 ft. Staying hydrated will be important as it helps the acclimatisation process.

In addition to the thin air, which will mean that I will have to run much more slowly than I am accustomed, the temperature is likely to reach 30 degrees Celsius by the finish of the marathon. Such hot temperatures will also negatively impact running performance regardless of the low oxygen, and low humidity levels (the Atacama Desert is one of the driest places on the earth). Therefore, hydration is doubly important, as is having the discipline to slow down and pace conservatively.

Back to the hypoxic training sessions: I have managed to do approximately one per week since August. We have had 2 main objectives: provision of regular exposure to hypoxic air in order to encourage the body to adapt more readily to it; and to determine a pace that I can comfortably maintain throughout to ensure that I complete the marathon.

During the sessions I breathe the relevant mix of air from a large bag through a mouthpiece, with my nose clipped. I wear a heart rate monitor and a blood oxygen monitor. Whilst the oxygen content of the high altitude air can be replicated using this method, the thinness of the air cannot.

My first session was ‘at rest’, simply sitting breathing a mix of air with 11% oxygen in it. I coped well without developing any of the common symptoms of being at high altitude, other than a very slight lightheadedness. As expected, my heart rate elevated and blood oxygen saturation level dropped, and I found that I had to breathe more deeply.

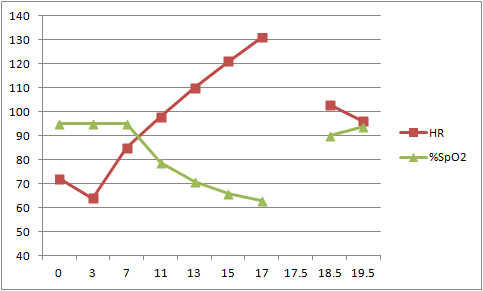

That session went so well that on the 2nd session we decided to try walking on the treadmill. After barely 6 minutes of walking the test was stopped as I was starting to stumble. I did not feel ill in any way, but just could not get my legs to do what I wanted: it felt as if I was drunk. My heart rate had elevated rapidly and my oxygen saturation had dropped quickly too.

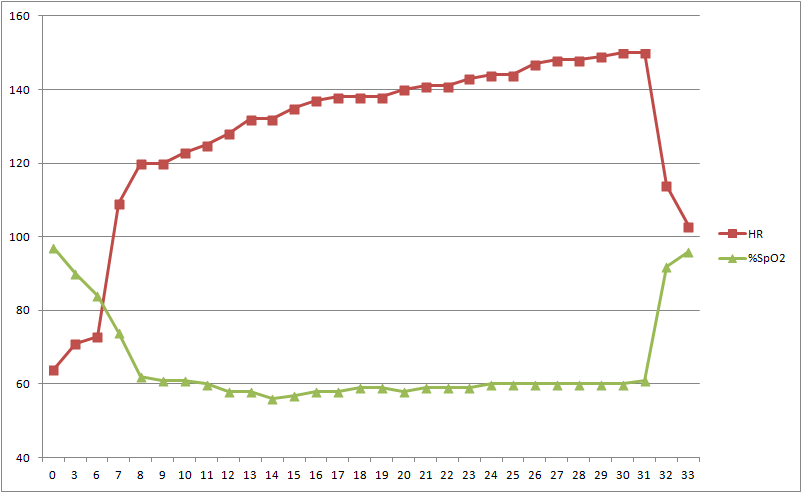

Neither Nairn nor I had expected my body to respond quite the way it did. After 10 – 15 minutes of recover, and not to be deterred I asked if he would be prepared to let me try cycling and he agreed. We kept the effort light, but I managed about 25 minutes cycling comfortably on the hypoxic air. My oxygen saturation settled in the high 50s (%) and my heart rate elevated steadily with the duration of time to high 140s. As with the at-rest session I only experienced very minor lightheadedness and no headache or nausea. My breathing did become harder towards the end of the session. The effort was only set to 50 watts but it felt harder than that, just because my body had to work harder to get the oxygen to where it was needed.

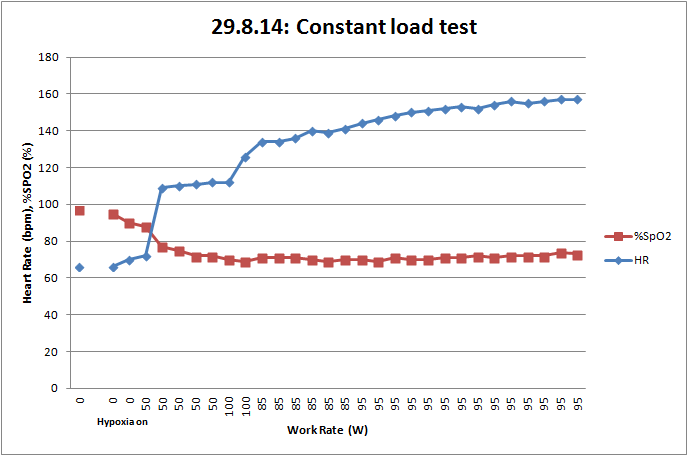

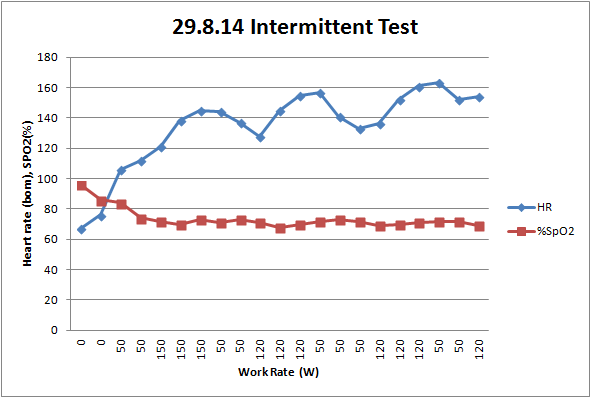

We decided to stick with the bike for the 3rd session and go for a constant load in terms of effort, although we played with it a little to find a level that I felt I could sustain. My oxygen saturation levels settled in the low 70s and my heart rate elevated with the effort, but settled. After 35 minutes the bag of air was empty. It was re-filled and we decided to try an intermittent load test. This was interesting. We found that my oxygen saturation settled in the low 70s and was not affected by the increases and decreases in effort. My heart rate on the other hand did respond to the intervals. Again, I was told to expect it to feel hard and it did. I could feel my muscles starting to burn and my breathing become more laboured.

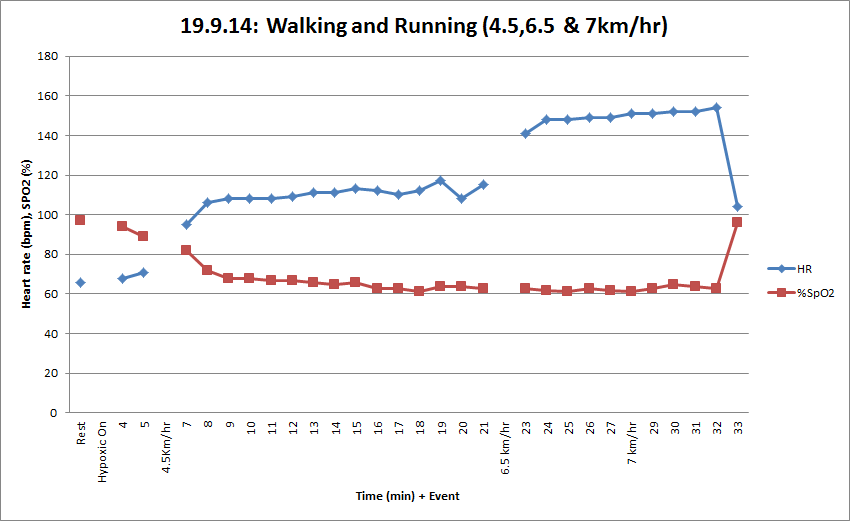

Time to get back on the treadmill, and for the 4th session we decided to start off with a walk and if things were going well increase to a run/slow jog. The session did go well, and we went from 4.5km to 6.5km and finally to 7km per hour. We could see a pattern forming now with my stats. My blood oxygen saturation would drop and level out irrespective of level, in this case low 60s, and my heart raise would elevate and settle according to effort, but be high in relation to the level of effort. Again, no altitude symptoms other than how hard it felt.

There is a voice in my head that says ‘this is a slow plod, so why is it feeling so hard’. The voice in my head also says, ‘I want to go faster’, but the problem with that is the elevation in heart rate. My theoretical maximum heart rate is 169 bpm, and yes, I could run with my heart rate sitting at that, but I will not be able to sustain it. After a very short while my body would force me to stop. I should be aiming to keep my heart rate somewhere roundabout 145 bpm.

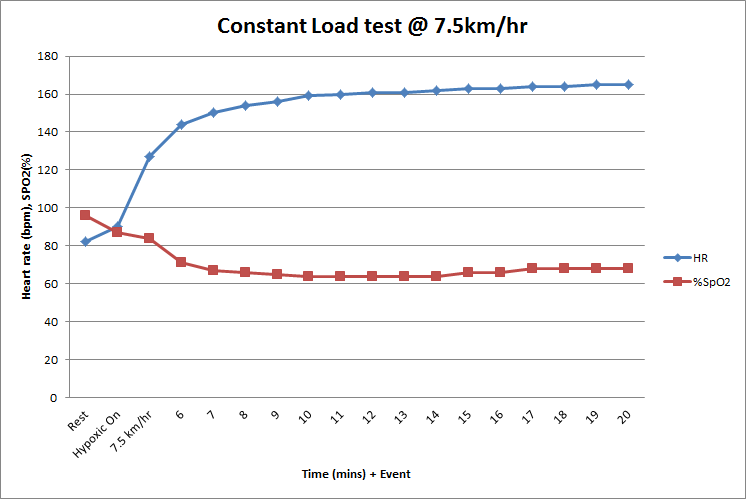

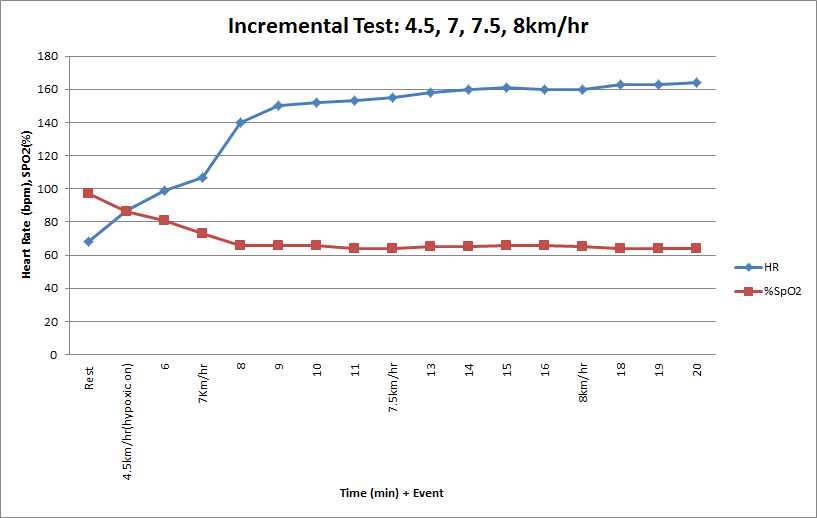

In session 5 we played with the speed, ranging from 7km to 8km. When I got up to 8km there was a marked increase in my perceived effort and my heart rate was up close to maximum. It was beginning to look as if I will only be able to sustain a pace in the region of 7 – 7.5km. Even for someone who is slow, that is slow. Session 6 went back to a constant load running at 7.5kmph for about 20 minutes. The air bag capacity is 1k litres and when running it empties in about 20 minutes. This felt comfortable and steady. My blood oxygen saturation was steady dropping to low 60s but starting to increase towards the end of the session. My heart rate was also steady between 160 and 165, still a bit too close to my maximum.

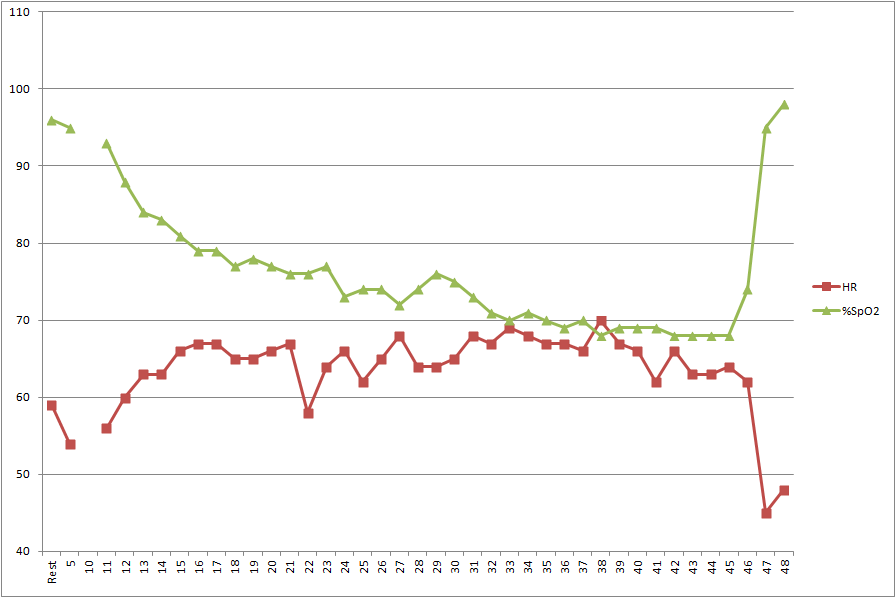

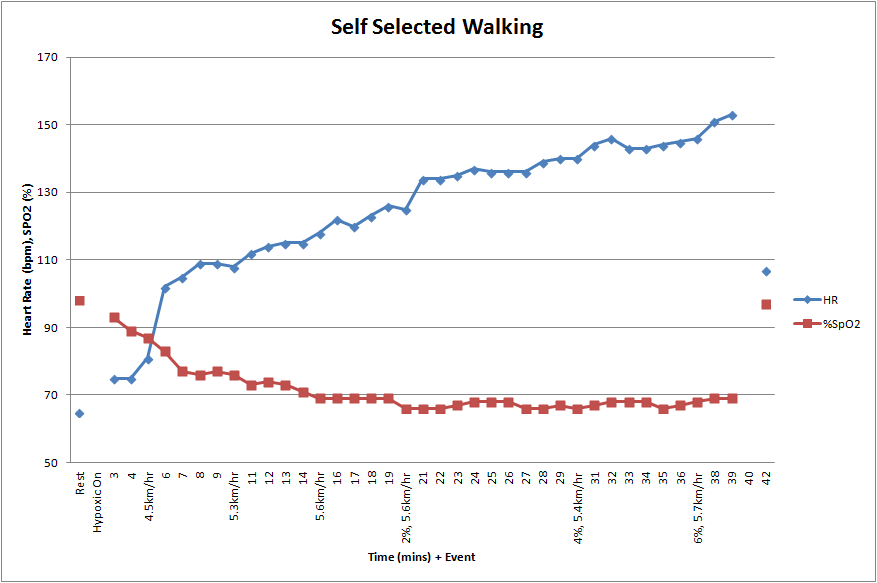

Two further constant load sessions followed and my body is adapting and responding well, and managing a slight increase in pace to 7.8 with little effect. In session 9 we decided to aim for a longer exposure with a walking session. During this session I controlled the speed and incline and so decided to experiment with some gentle inclines and walking at roundabout my ‘ultra yomp’ pace. As previously seen my heart rate responded to the changes of pace and incline and again my head struggled to rationalise the perceived effort with the actual effort.

The most recent session was done with a different mix of air, setting it to the equivalent of the altitude after the first decent on the route. An extra 1% of oxygen makes a difference, and I can pick up the pace slightly. I have 3 more sessions before I go to Chile and the plan with these is to have one session where the air is the equivalent of the finishing altitude, and a further 2 walking sessions for longer exposure.

Has this been worthwhile? In a word, yes. I have learned how my body will respond to the low oxygen levels in the air, and through this exposure it is hoped that I will acclimatise quickly and more easily when I get there. It has also shown me that I will have to be disciplined, I will not be able to run at any decent pace, and that if I monitor my speed and heart rate and keep within the advised parameters I will be able to keep a steady pace. That will be the key to not risking a crash and burn and to being able to acquit myself well and finish. And yes, we are simply going for a finish on this one.